The Theory of (N)everything

- Feb 2, 2018

- 9 min read

Updated: Jul 19, 2021

My fascination with Physics has grown in parallel with my interest in Philosophy. Debates arise as to the merit of either discipline in the understanding of our world. I see no distinction of importance between the two (Carlo Rovelli: Why Physics needs Philosophy) as I maintain that the empirical and the metaphysical are equally crucial for the understanding of the universe. Without the right questions, we would never find the right answers.

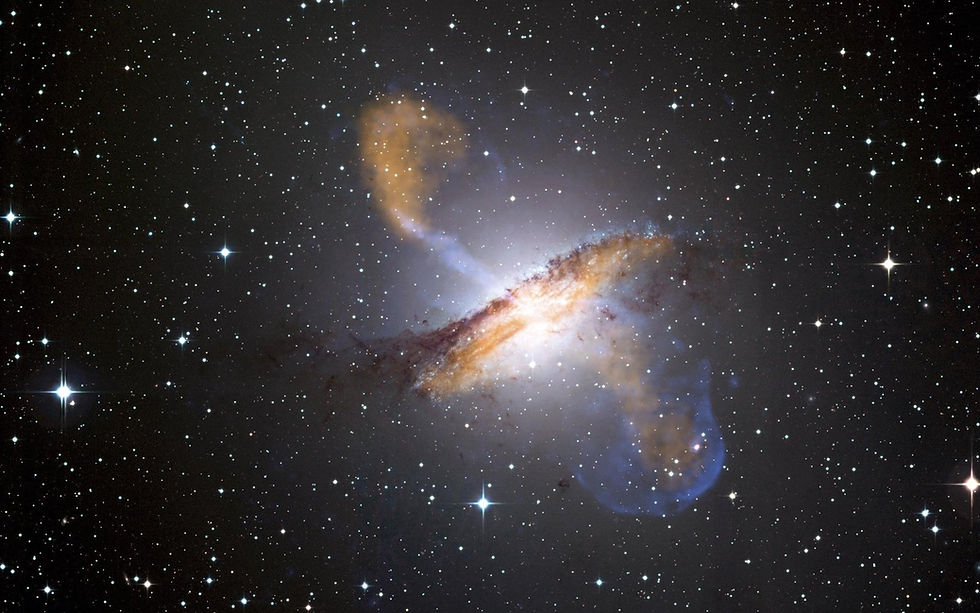

As things became very small with the study of Quantum Mechanics, a link was needed to the very massive (Einstein's Theory of General Relativity), in what is supposed to become a Theory of Everything, also known as Quantum Gravity. I've played with the idea and philosophised about it and these are some of my musings, which I call the Theory of (N)everything. The silly title is to emphasise my total awareness of my shortcomings both in scientific and philosophical terms.

In the beginning, there was coffee. Scattered coffee, to be precise. One spring morning I was preparing the brew the Italian way, with a little espresso maker. Inevitably, as I piled and pressed the grains into the metal holder, some of them spilt over onto the tabletop, and without a second thought, I brushed them off, sending them onto the floor (I swept it all up afterwards, honest). A thought occurred to me then: if I could shrink to the size of bacteria and I found myself in front of one of those grains, what would I know about it? The kitchen floor would be the equivalent of a sizable portion of the universe and a grain of coffee that of a small planet. I would know nothing about other grains, let alone their distribution in the surrounding emptiness. After the equivalent of hundreds of years later, my bacterial descendants might find the next coffee grain and record the distance between the two. Then another, and another and so forth, until enough information would start to form a picture, not only of the number of grains but also of their most likely provenance (the Big Bang if you like), as they would be more scattered in one part of the room and clumped together in the opposite direction (origin point). The same thing happens in space. What we see or detect is information. All the information since the beginning of time (or the infinite) has been there for us to gather and analyse. From that data, we have formulated theories, laws, and speculations as to the nature of the cosmos and its life within. We are also made of information and how we work is down to its synergy with the entropy it creates. This is what reality (consciousness) is to us (but not necessarily what it is): a processing, filtering and subsequent derivative of the multitude of interactions... but also our soul and/or the result of the connection between body-brain and the universe around us.

With a limited understanding of how we are created and function, we have pursued to measure and quantify ourselves and the world around us. One of these fundamental measures is Time. Over the centuries and up until recently we have thought of Time as an inalienable measure of past, present, and future. We have calculated it according to our own experiences (life) and the observable universe. Thus, we have devised hours, days, months, etc as benchmarks of our connection with the Sun, our source of life. We have a concept of beginnings and ends because we are born and die. Our cells produce that transformation and as we experience it we give it a meaning, scientific or spiritual. But our life on Earth is only a tiny fraction of the life of the planet itself. We've been around, as modern humans, for about 0.2 million years and our ancestors for 6 million years. That's only 0.13% of the age of our planet (4.5 billion years). In cosmic terms, not a lot. But at the beginning of the 20th century, time became entwined with space in the fabric of the universe, as spacetime. We now know it's elastic throughout space as it stretches around gravitational objects (proved by the recent detection of Einstein's brainchild: the gravitational waves).

Time, in human terms, is simply an anchoring system, where the values have been arbitrarily chosen and averaged as to be usable. According to Christophe Galfard in his book The Universe in your Hand, reality can't ever be known exactly; observations and experimentations, however accurate, always give an approximate answer with an error margin. There's always something in between two points of reference. Our understanding of that limitation manifests itself in the use of averages in our collective imagination. Average, because the very numbers that are used to measure are arbitrary.

One way to visualise this is to think of the old-fashioned electricity meter, the one with dials as shown in the picture below. The arm in the first dial rests on the 6. Is it really on the 6, or the 5? To be sure we then look closer at the unit's subdivision on its right. The second dial says it's past the 0, and towards the 1, so the previous dial cannot be a 5 anymore but inside the 6 towards the 7. If even the second dial had been unclear, we would've moved on to the third dial and so on. Until we choose how accurate we need to be.

Comments